Welcome to the Wadsworth Area Historical Society‘s website where we are committed to preserving the history of Wadsworth and surrounding areas.

Thanks to you the historic St. Mark’s Church is now paid off!

Thanks to all of our kind supporters and donors over the last several months we have finally reached our goal of $225,000 to pay off St. Mark’s Event Center. We will still be taking donations until April 1 of 2026 to help cover future expenses. We are so grateful to all of those who contributed not just financially, but with their time and efforts. Being the oldest church structure in town (built in 1841) we are so thankful to all of our contributors that have helped save this historic building. Thank you all!

You can also find us on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/WadsworthAreaHS/

St. Mark’s Event Center is located at 146 College St. Wadsworth OH 44281

The Johnson House Museum is located at 161 High St. Wadsworth OH 44281

For more info contact Roger L Havens 330-336-5548 or send an email at Wadsworthareahistoricalsociety@gmail.com

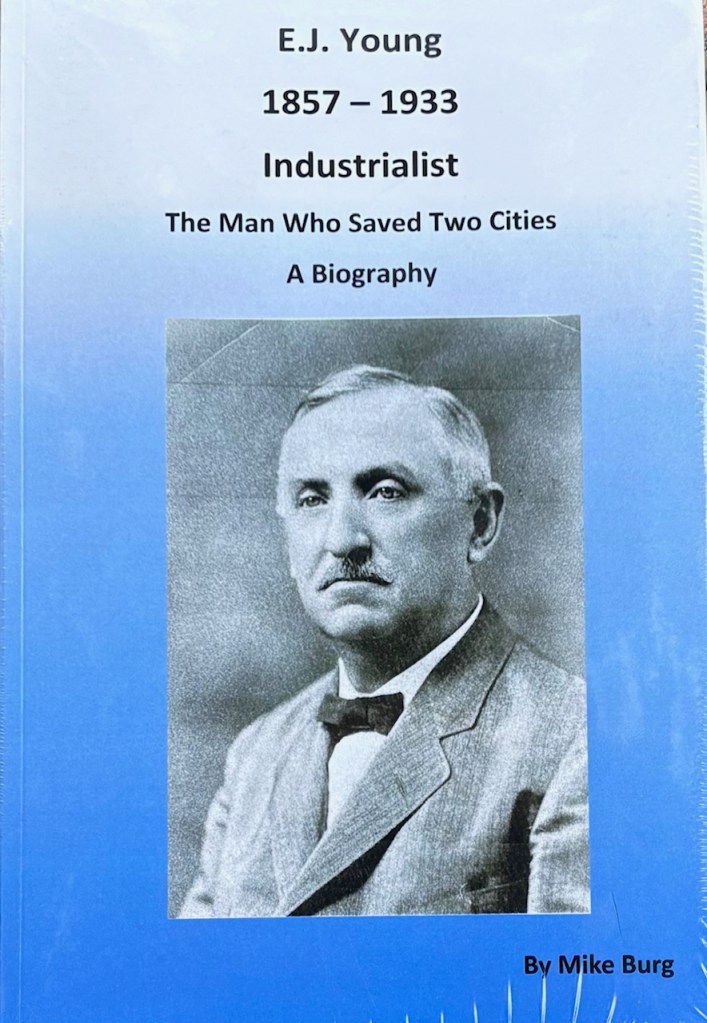

Wadsworth historical books for sale at the Johnson House Museum that is open every Saturday 10:00 am to 12:00 am, the Water Main Grille and at The Book Shelf!